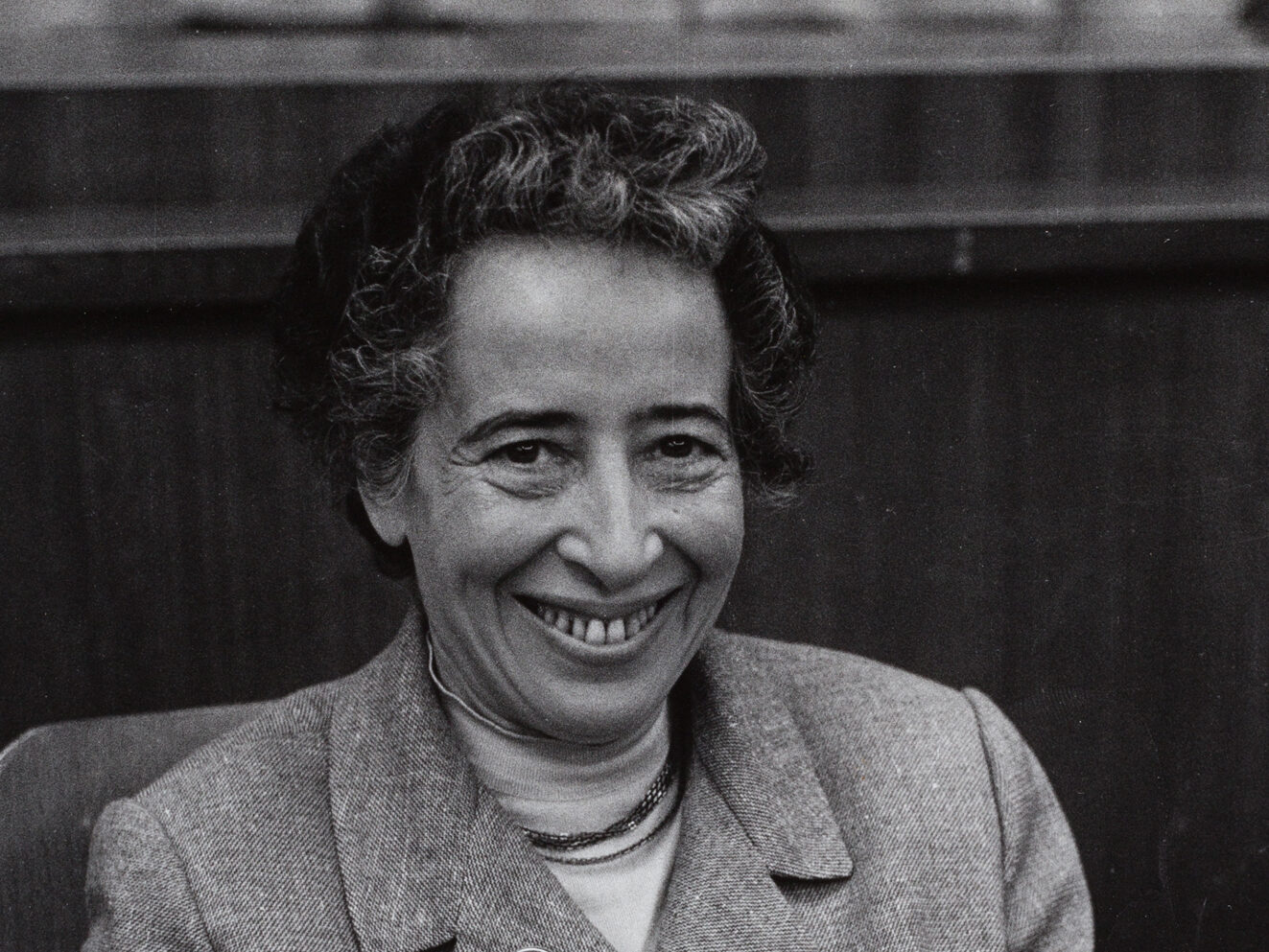

Hannah Arendt 1958

CC BY-SA 4.0; Münchner Stadtmuseum, Archiv Barbara Niggl Radloff

Immediately after the end of the war in 1945, Hannah Arendt wrote a text entitled Organized Guilt. It was one of the first attempts to politically and conceptually grasp what could no longer be denied: the “administrative mass murder” of millions of people and the systematic and industrially operated attempt to destroy European Jewry. As Arendt wrote, this did not require “thousands of selected murderers” because “total mobilization” implied everyone and thus resulted in the “total complicity of the German people.”

Arendt did not write as a historian or impartial witness, but as a political thinker. As someone who looks – and judges. “To live truly is to realize this present,” she noted a few years later. She asked how it had been possible for so many to participate and so few to object – and why, after unconditional surrender, so many simply wanted to forget.

Her thesis: under Nazi rule, guilt was not covered up or suppressed, but organized. It was divided up, depersonalized, morally gutted—in order to destroy responsibility. The line separating the guilty from the innocent, Arendt writes, was blurred so effectively that it became almost impossible to distinguish between those who committed the crimes and those who opposed the killings. It is not the individual who bears the burden of injustice, but everyone—and thus no one.

“Everyone just did their duty,” said the perpetrators—without cynicism, without remorse. The real achievement of totalitarianism lay in the production of fellow perpetrators. They know and feel no responsibility and perceive themselves merely as part of an apparatus, an order. Arendt quotes a camp accountant: “Did you personally help kill people? Not at all. I was just the camp’s paymaster. What did you think about what was happening? At first it was bad, but we got used to it.”

When guilt becomes a function, thinking becomes a disturbance. That is precisely Arendt’s point. Conscience was not eliminated, it was reshaped. Language was not destroyed, but recoded. Words such as “Final Solution,” “evacuation,” and “resettlement” served not to deceive, but to exonerate. It was possible to participate in the conversation—without knowing. Or rather, without wanting to know.

This diagnosis points to the essence of the modern state and its bureaucracy, which integrates every action into a system in such a way that no one needs to say, “I am responsible.” That was Arendt’s early warning—and it is more relevant today than it has been in a long time. Today, we find ourselves in a situation in which we are no longer just witnesses, but accomplices, participants in the blurring of the boundaries of violence and the obfuscation of responsibility.

It is not only since October 7, 2023, that we have been caught up in a dynamic that eludes any moral language—and at the same time is legitimized by language. International law guarantees the right to self-defense—for Israel as well as for the people of Palestine. It obliges states and armed groups to protect the lives of civilians. The Hamas attack on civilians, which has not yet been fully investigated, and the abduction of hostages to Gaza were crimes against humanity and must be punished as such. However, the fact that the shock and threat to Israeli society – and to Jewish communities worldwide – has been taken as a blank check to respond with further escalation of violence is driving the dynamic into the abyss.

In Gaza, it can no longer be denied that systematic efforts are being made to destroy the Palestinian people’s right to life, both as a whole and in parts, through the complete destruction of all infrastructure, the starvation of the population, the mass killing of civilians, and the destruction of their natural resources. A besieged death zone—without refuge, without escape, without a future. An ever-growing number of genocide researchers and international law experts have concluded that the criteria for genocide have been met.

And the language? It works perfectly. It speaks of “precise strikes” or “surgical operations” where civilians are dying in their thousands. Every child killed is potentially a “human shield” or a terrorist in the making. It repeats like a mantra: “Israel has the right to defend itself” – and allows us to sidestep the question of how far this right extends, what it outweighs, where it ends. It asserts: “We are doing what is necessary,” and makes us forget that we are the ones who continue to supply weapons.

Once again, responsibility is being organized so that no one is responsible. The US supplies weapons, resources, infrastructure, and propaganda support, and during Joe Biden’s presidency, it sometimes declared that it had “red lines,” but these could be crossed without consequence. The UN warns, counts, documents—but its resolutions fall on deaf ears. The EU struggles to find the right words and is divided. The German government also supplies weapons, stands in solidarity with the Israeli government even where civilian life is systematically devalued and destroyed, and only expresses “criticism” when international isolation threatens—criticism that remains largely without consequence.

Responsibility is not openly denied—it is distributed, blurred, relinquished: through participation, through language, through silence. Structural violence—decades of occupation, blockade, the systematic destruction of infrastructure and resources long before October 7—gets ignored. Instead, a rhetoric of necessity and moral self-assurance dominates.

Arendt knew that anyone who wants to defend political thought must defend language. Not as ornament, but as a place of judgment. She showed how dangerous it is when terms lose their moral core—and how necessary it is to maintain distinctions: between perpetrator and victim, attack and defense, proportionality and the will to destroy.

Today, we are experiencing a linguistic regression: criticism is dismissed as mere worldview, and naming violence is considered a threat. Anyone who draws attention to the injustice against the Palestinians is suspected of anti-Semitism. Those who insist on injustice are supposedly endangering security. This reversal narrows the scope of what can be said—until defending the world in Arendt’s sense becomes impossible. For what does not appear cannot become the object of collective action. Where the sayable dwindles, the real is redefined—in the language of war, reality is not described, but made. Terms such as “human shields” ultimately place the blame on the victims. Those who describe a complete siege as “self-defense” shift the blame to where the dead were buried.

This language is functional. It creates distance, moral relief, approval. In press releases, government statements, and social media, it becomes ammunition: “terror infrastructure,” “safe zones,” “precise operations.” Each of these words stands between us and reality and prevents us from realizing it, as Arendt demanded.

And this is where history and the present intersect: Arendt’s text was written when the images from the camps were still fresh and Auschwitz was not an abstraction but an immediate reality. She wrote against collective blindness, against the willingness to move on to the agenda of the day. Not in the name of the past, but in the name of a future that was to be different. Today, historical guilt is frozen, without leading to any present political responsibility. Auschwitz has become moral property. The descendants of perpetrators now act as guardians of memory—and derive from this a responsibility that relates solely to Jewish life, not to the Palestinian life under bombs. This is not a lesson from history—it is its instrumentalization.

Arendt rejected any sacred inaccessibility of history. Memory that does not lead to judgment and action becomes a moral pose: “Never again.” Arendt would have asked critically: Never again what? Only Auschwitz? Or any dehumanization, expulsion, deprivation of rights? She argued for a plural and differentiated conception of responsibility—not exclusive, but inclusive: Those who learn from Auschwitz cannot legitimize disenfranchisement anywhere. Auschwitz must remain a radical ethical warning: Every form of dehumanization must be named, even if it originates from a state to which Germany has a historical obligation. Especially then.

Arendt distinguished between guilt and responsibility. Guilt concerns perpetrators. Responsibility concerns everyone who is part of a political order and obliges them to think critically, to differentiate, and to exercise judgment. It does not arise from identity, but from being part of the world. Those who live in a political order bear shared responsibility—not because they are all perpetrators, but because they are all members of that order.

Arendt would not have asked for solutions, but for spaces for action in which responsibility is shared, violence is named, and alternatives become audible. Such spaces exist on both sides, Israeli and Palestinian, and in the best case also connect both sides. But their existence is also threatened. In 2021, Israel banned six Palestinian human rights NGOs, including Al Haq in Ramallah, an organization that has documented human rights violations in the occupied territories for many years – committed by both Israel and Palestinians. The language of “security” and “counterterrorism” has been and continues to be used to justify the ban on these NGOs. This language has long been extended to Israeli NGOs that advocate for the rights of Palestinians. Breaking the Silence and B’Tselem were accused of being “traitors” as early as 2016. A new Israeli tax law seeks to impose an 80 percent penalty tax on foreign (Western!) donations to Israeli NGOs. In April, the Israeli police banned the organization Standing Together from showing pictures of Palestinian children killed in a demonstration. And in January, the former German federal government revoked the foreign policy clearance and eligibility for funding of the peace activist organizations Zochrot and New Profile in the middle of their ongoing project period.

None of this serves Israel’s security – quite the contrary – but it suppresses opposition to human rights violations. The language that obscures those weakens our judgment. Being able to judge is perhaps the most important political virtue, wrote Arendt. It is not loyalty that protects democracy, but the ability to distinguish. Those who want to learn from history must not be content with remembrance. Now is the time to act. To speak anew. To speak clearly. Because reality must not be defused by euphemisms. Arendt knew this. Those who speak of Gaza today should take her at her word.