Naomi Klein: „How Israel Has Made Trauma a Weapon of War“, The Guardian, 5. Oktober 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2024/oct/5/israel-gaza-october-7-memorials.

Ben Ratskoff: „Prosthetic Trauma at the Nova Exhibition: Holocaust Memory, Reenactment, and the Affective Reproduction of Genocidal Nightmares”, Journal of Genocide Research, 2. September 2025, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623528.2025.2551946.

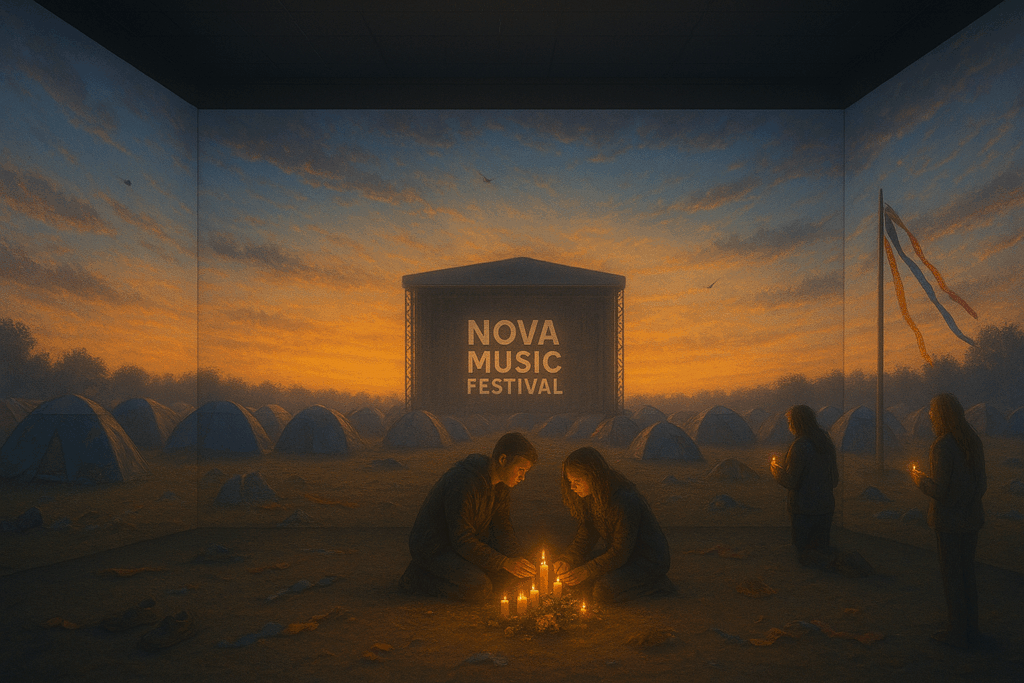

The traveling exhibition “The Nova Music Festival Exhibition” (motto: “06:29 –The Moment the Music Stopped”) has been touring the world since the end of 2023. Previous stops were: Tel Aviv, New York, Los Angeles, Miami, Toronto, Boston. According to the website of exhibition and theme park designers Breeze Creative, it “reconstructs” the massacre of Palestinian combatants among the participants of the open-air trance party near Kibbutz Re’im on the morning of October 7, 2023 (in which an estimated 378 people died and another 44 were taken hostage), “using authentic objects collected shortly after the events — including burned cars, bullet-riddled portable toilets, abandoned camping tents with personal belongings inside, and the possessions of those murdered or kidnapped. Alongside these are gripping visual media: survivor testimonies, videos, and images capturing the horror.” “The Nova Music Festival Exhibition” was produced by the founders of the Nova Music Festival and the companies of Israeli cultural event organizer and festival founder Yoni Feingold. The Israeli government provided support from the outset, as did politicians in the host cities and many Jewish organizations. However, large sections of the Israeli population and the families of the hostages were and remained less unanimous. It is all too obvious that the Nova exhibition is enlisted as part of the Israeli government’s public diplomacy work, which it itself refers to as Hasbara, or Zionist propaganda. On the other hand, the exhibition is set in a context in which propaganda, information, documentation, and serious research are often difficult to distinguish from one another.

Now “The Nova Music Festival Exhibition” is coming to Berlin-Tempelhof, to the former airport building, under the patronage of Governing Mayor Kai Wegner, as announced in the local press on September 5. The announcement and the media coverage that is expected to be following makes it seem sensible to prepare by taking a closer look at the history, ideological implications, and curatorial strategies of this enterprise. Two texts are particularly recommended: “How Israel Has Made Trauma a Weapon of War” by Naomi Klein, published last year in The Guardian, and the essay “Prosthetic Trauma at the Nova Exhibition: Holocaust Memory, Reenactment, and the Affective Reproduction of Genocidal Nightmares,” published in early September of this year by Ben Ratskoff, a researcher in memory culture and the politics of the past. Klein and Ratskoff situate the exhibition project in the broader context of historical politics and memory culture activities in response to the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023, both within and outside Israel. Plays, films, a television series, VR online videos (such as the “Gaza Envelope 360 tour”) and themed tours of the dark tourism variety transform the traumatic events into various forms of visceral, immersive entertainment. Most of these products aim to draw views and visitors emotionally into the events of that day. The primary goal is to identify with the victims, to empathize with their suffering and death. At the same time, the effort involved in detailed documentation is often very impressive, and there are also more nuanced attempts to respond to the events of that day and its aftermath. However, as Klein argues, these products and the discourse surrounding them, consistently fail considering the research conducted in recent decades on the “ethics of memorializing real-world atrocity” and its eminently political dimension. Instead, the memory industry seeks to unilaterally dissolve the “difference between inspiring an emotional connection and deliberately putting people into a shellshocked, traumatized state, ” namely in the direction of “immersion”: “offering viewers and participants the chance to crawl inside the pain of others, based on a guiding assumption that the more people there are who experience the trauma of October 7 as if it were their own, the better off the world will be.” Another, similar yet crucial difference is that between “understanding an event, which preserves the mind’s analytical capacity as well as one’s sense of self” and “feeling like you are personally living through it.” The latter can be called “prosthetic trauma,” using a concept introduced by the historian Alison Landsberg (Prosthetic Memory: the Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture) and the sociologist Amy Sodaro (Exhibiting Atrocity: Memorial Museums and the Politics of Past Violence).

Ben Ratskoff likewise draws on the concept of “prosthetic trauma.” His meticulous description and analysis of the Nova exhibition leads to the conclusion that Klein’s criticism of the historical-political instrumentalization of October 7 is just as valid as her objections to the breakdown of reflective distance in the mode of immersion: “Offering the pain and suffering of real victims as a simulated experience for public consumption, the Nova Exhibition underscores concerns that reenactment as a discursive mode and exhibitionary strategy obliterates the critical distance necessary for ethical reflection and contextualized understanding while nourishing destructive (and self-destructive) narrative panics and existential anxieties.” Ratskoff further emphasizes that such treatment of the memory of atrocities tends to reproduce rather than prevent genocidal nightmares, especially when the rhetoric and formats of Holocaust remembrance are transferred to the events of October 7, 2023: “Tropes and patterns drawn from Holocaust memory and the memorial museum form construct a powerful apparatus of emotional identification that blurs the figurative and the real, and memory and actuality.”

Wherever individual and collective acts of violence and experiences are “commemorated” institutionally, a gap has been widening for decades. State agencies and private-sector companies, often operating in public-private partnerships (as in the case of the Nova exhibition), that are involved in (trans)national remembrance and political education are torn between, to put it simply, education and explanation on the one hand, and emotionalization and identification on the other. Increasingly, the decision is being made in favor of the latter, of immersion. Since renowned historical museums such as the Imperial War Museum in London began staging the trenches of World War I and the bombing nights of the Blitz like ghost trains, hardly any major institution believes it can do without gamified exhibition concepts. Museums and memorials dedicated to the Holocaust, above all Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, have long been confronted with these expectations of immersive re-experiencing of the trauma and are giving in to them.

Regardless of the particularly charged events of October 7, 2023 and their commemoration, one might therefore ask: What are the functions and effects of the methods and technologies aimed at immersion and reenactment, which are increasingly being used in various contexts of memory culture, education, and therapy? When does the offer of identification turn into propaganda, empowerment into mobilization? How may the collapse of (critical) distance brought about and practiced in this way affect entire societies? For the making-immersive of history and politics, as practiced (not only) in the Nova exhibition, entails a deceptive unambiguity. Immersion has become the default mode of remembrance, the formula for political communication that rhymes participation with passivity, agitates by staging trauma. Now, “The Nova Music Festival Exhibition” will be open to visitors in Berlin. Where else but in this city would there be an opportunity to reflect on the fact that the aestheticization of violence and the instrumentalization of trauma have already had devastating effects in the past?